Sumio Suzuki

An exhibition has been held at the Nagoya City Museum since September 10.

Approximately 200 valuable artifacts are on display, primarily excavated items from Shaanxi Province, which was the political center of both the Qin and Han dynasties in China.

In ancient China, people believed in life after death and buried figurines known as yong, modeled after humans and animals, together with the deceased. This exhibition features, among others, ten life-sized terracotta warriors from the unified Qin period, as well as a total of thirty-six figures of varying forms from different eras. Through these figures, along with bronze ritual vessels and weapons, visitors can gain a vivid sense of ancient Chinese history.

In 1965, nearly 3,000 terracotta warriors were unearthed from the burial pits of the Yangjiacun Han tombs near Changling, the mausoleum of Liu Bang, founder of the Former Han dynasty. Subsequently, in 1974, terracotta warriors were accidentally discovered during well-digging approximately 1.5 kilometers east of the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor. It was later revealed that about 8,000 figures lay buried underground. The discovery of the Qin terracotta army occurred during China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), and excavation did not begin immediately. Formal excavation of Pit No. 1 began in 1978, followed by Pit No. 3 in 1988 and Pit No. 2 in 1994. Inscriptions bearing the regnal era of the King of Qin (the First Emperor) and the name of Chancellor Lü Buwei were found on excavated weapons, leading to the identification of these pits as burial pits associated with the First Emperor’s mausoleum.

This study examines horses and horse tack separately during the Qin imperial period and the Former Han imperial period.

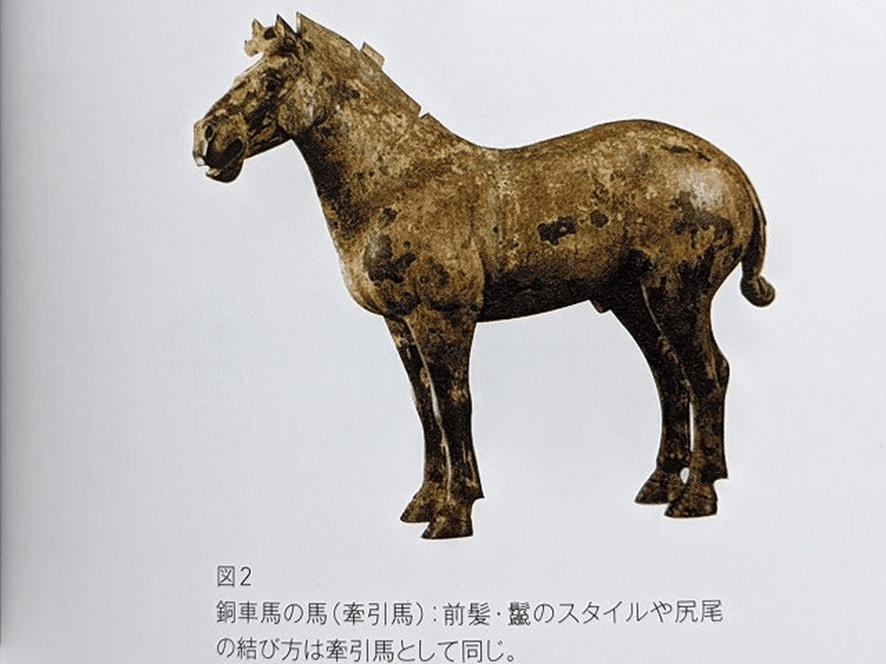

Horse bones excavated from the First Emperor’s mausoleum suggest a withers height of approximately 155 centimeters. DNA analysis indicates lineages originating from Central Asia and Europe. This suggests that, rather than the earlier stocky, large-headed, short-legged horses, the Qin people likely acquired western breeds at an early stage through active exchanges with northern nomadic peoples. With the rise of the Han dynasty, further improvements likely followed as new breeds were sought through the opening of the Silk Road.

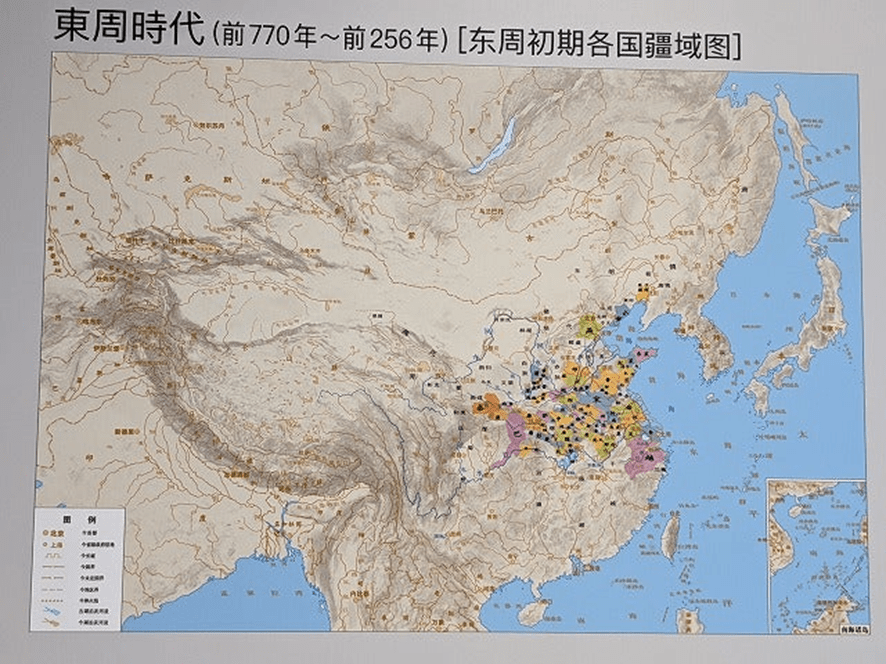

Qin dynasty: The First Emperor unified China in 221 BCE; the Qin fell in 206 BCE.

Former Han dynasty: Established in 202 BCE. Emperor Wu ascended the throne in 141 BCE, launched expeditions to the Western Regions’ oases in 104 BCE, and defeated Dayuan in 102 BCE (Note 1).

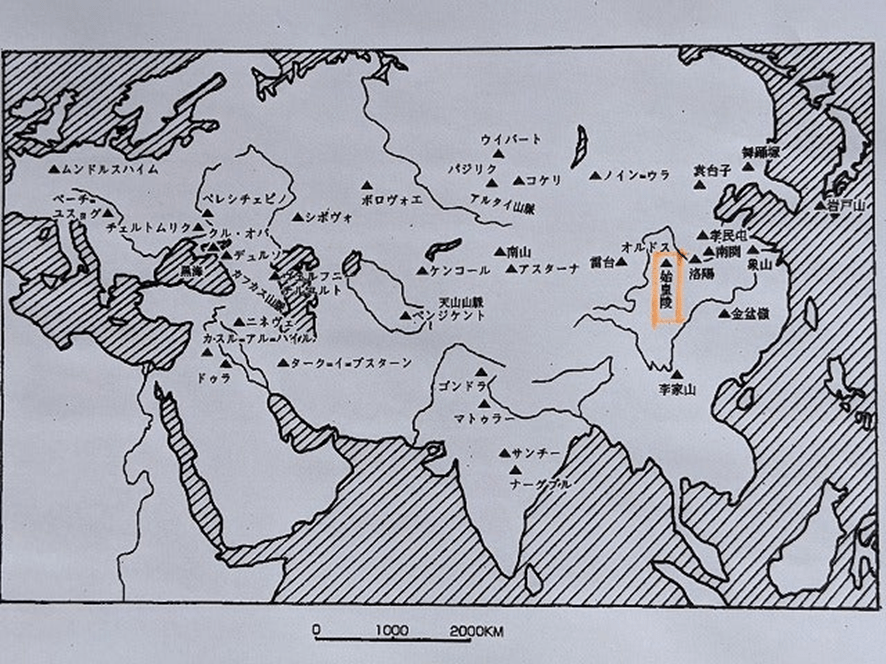

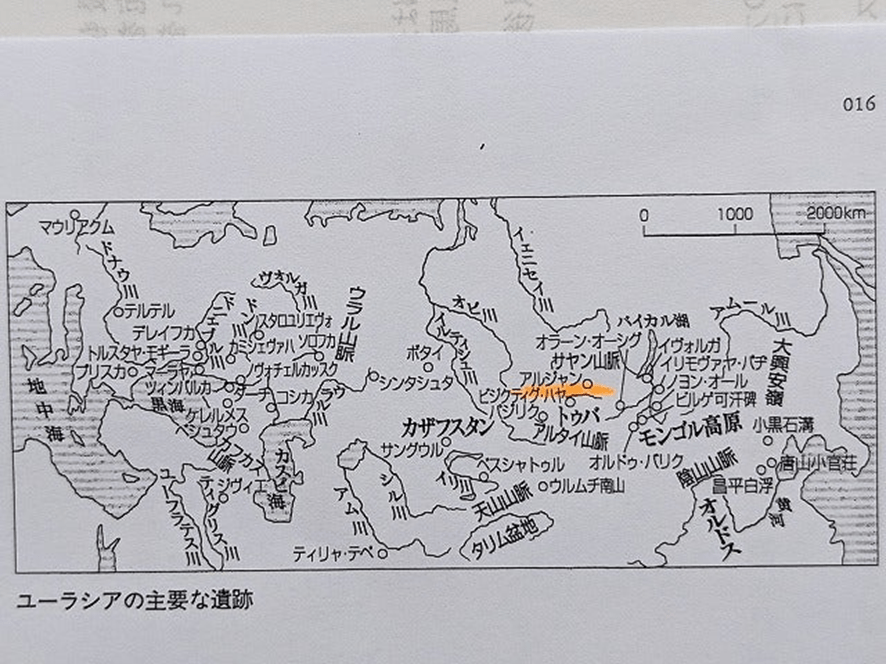

From the eighth to the seventh centuries BCE, vast grasslands stretching from the southern Russian plains to Central Asia gave rise to nomadic mounted states such as the Scythians, who used mobility and mounted archery to expand westward. During China’s Spring and Autumn period (770–403 BCE) and Warring States period (403–221 BCE), conflicts with these groups led China to absorb rich Central Asian and Greek cultural influences, culminating in the establishment of the Qin state.

While Qin culture retained a certain simplicity, it actively accepted talented individuals and advanced technologies from other states. The Qin script directly influenced modern Chinese characters, and with unification, the scripts of eastern states disappeared.

A. Qin Dynasty: Terracotta Army (Life-size Figures)

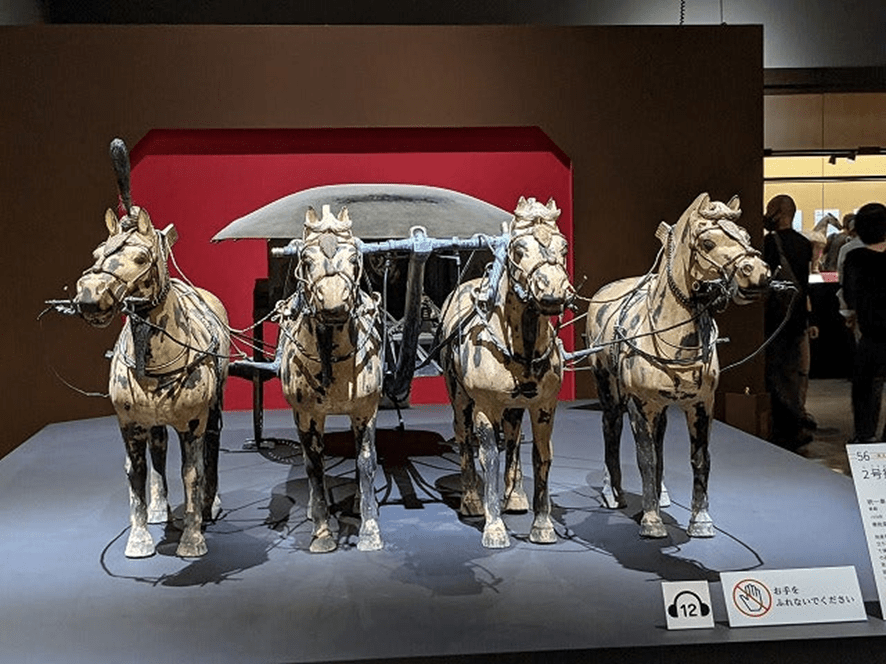

Bronze Chariot and Horses No. 2 (replica):

Height 106.2 cm; length 317 cm; width 176 cm.

The two bronze chariots were housed in wooden boxes, as if they had been buried intact. Because the burial depth was shallow at 8 meters, the wooden boxes decayed, and the chariot bodies were found crushed into fragments.

Horse of the bronze chariot

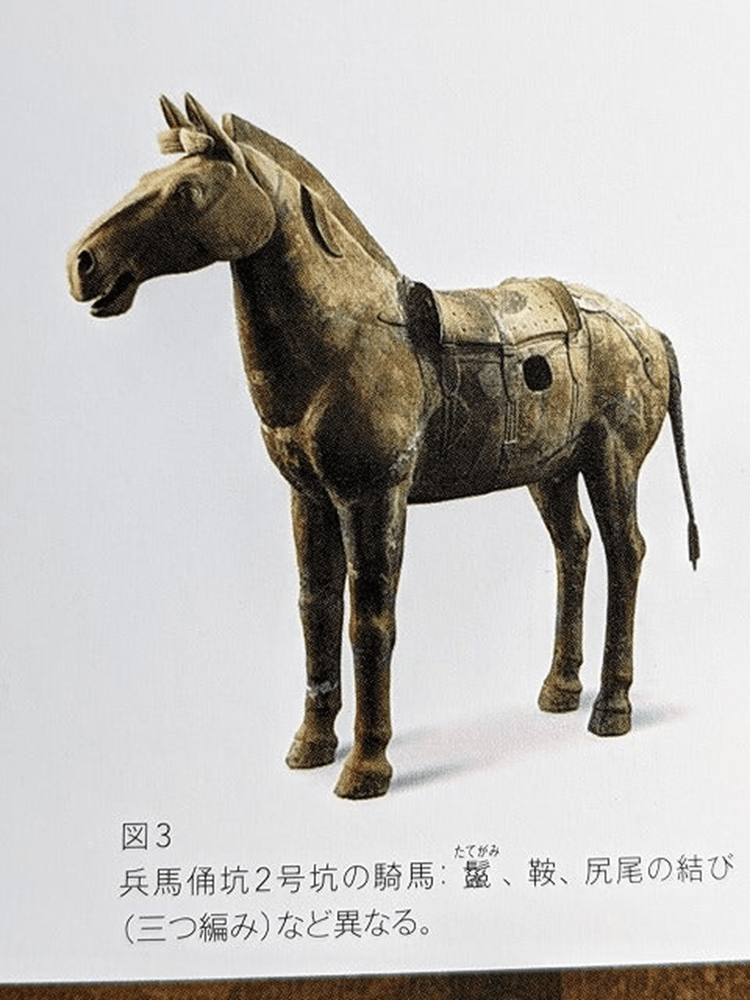

Mounted warrior from Pit No. 2

In the late fourth century, horses began to be imported from the Korean Peninsula to Japan. A “proto-horse skeleton” excavated from the Shitomiya-Kita site in Shijonawate City, Osaka Prefecture, has a withers height of 125 cm. According to The Genetic Background of Native Japanese Horses by Terasaki Akira, genomic data demonstrate that Japanese native horses share the same lineage as Mongolian native horses. However, as a researcher of Japanese native horses, I find it difficult to understand when and how such transformations occurred.

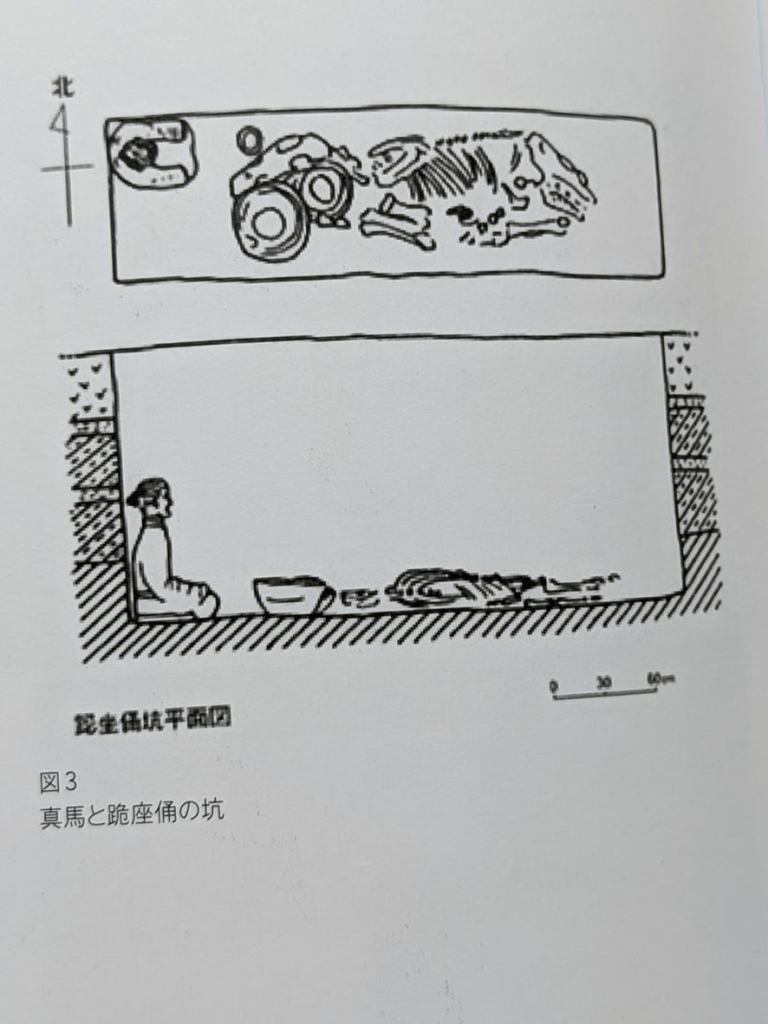

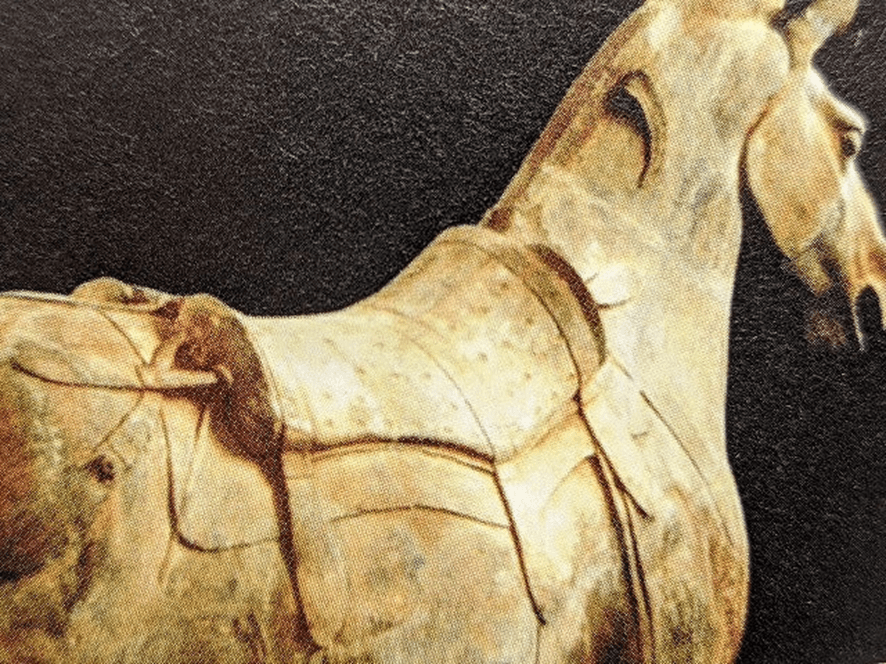

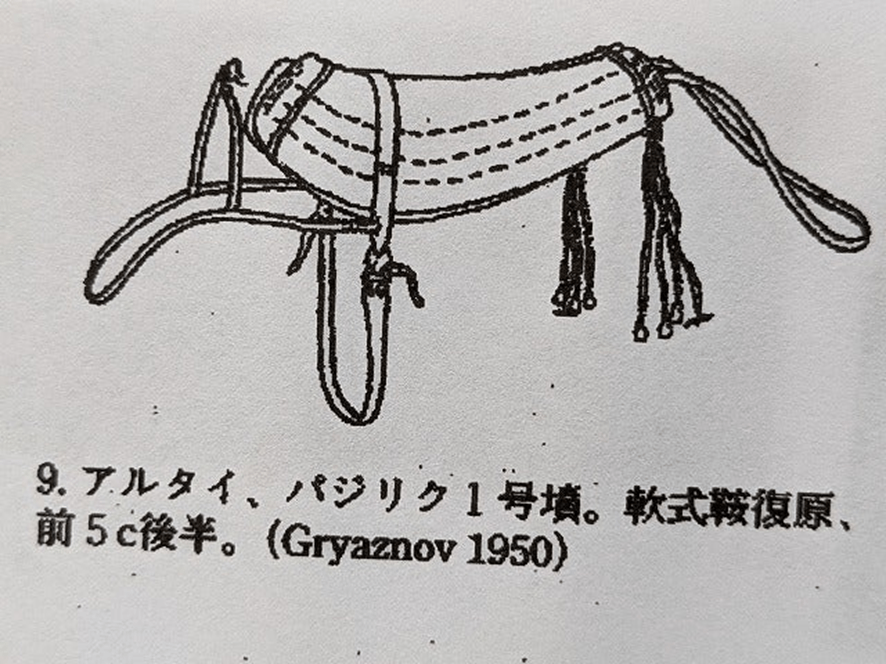

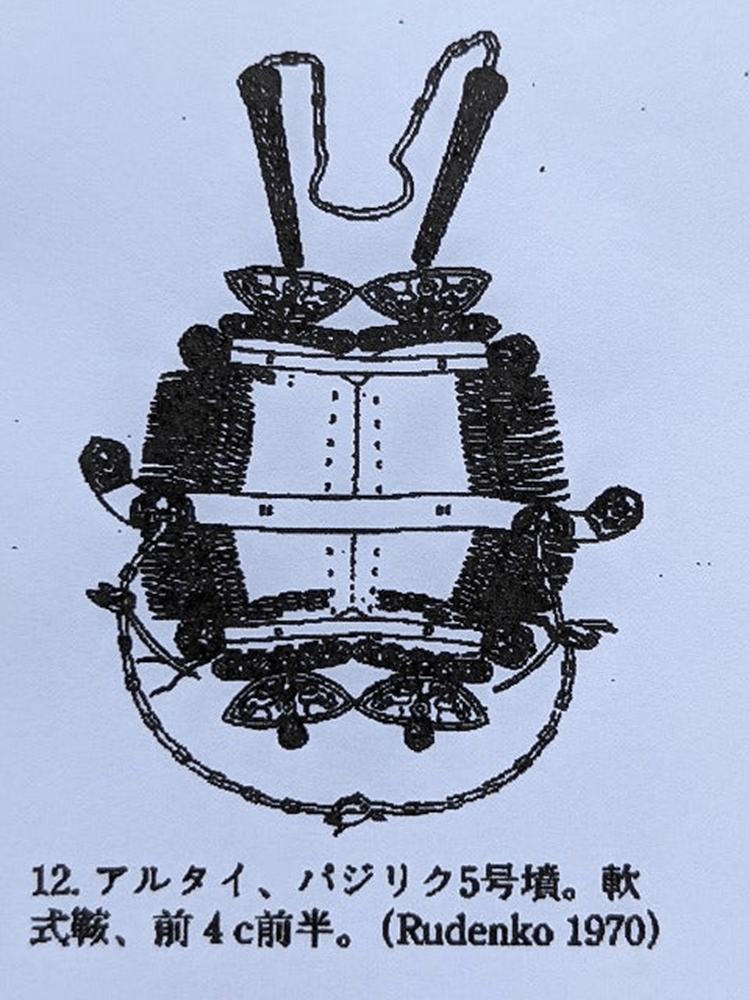

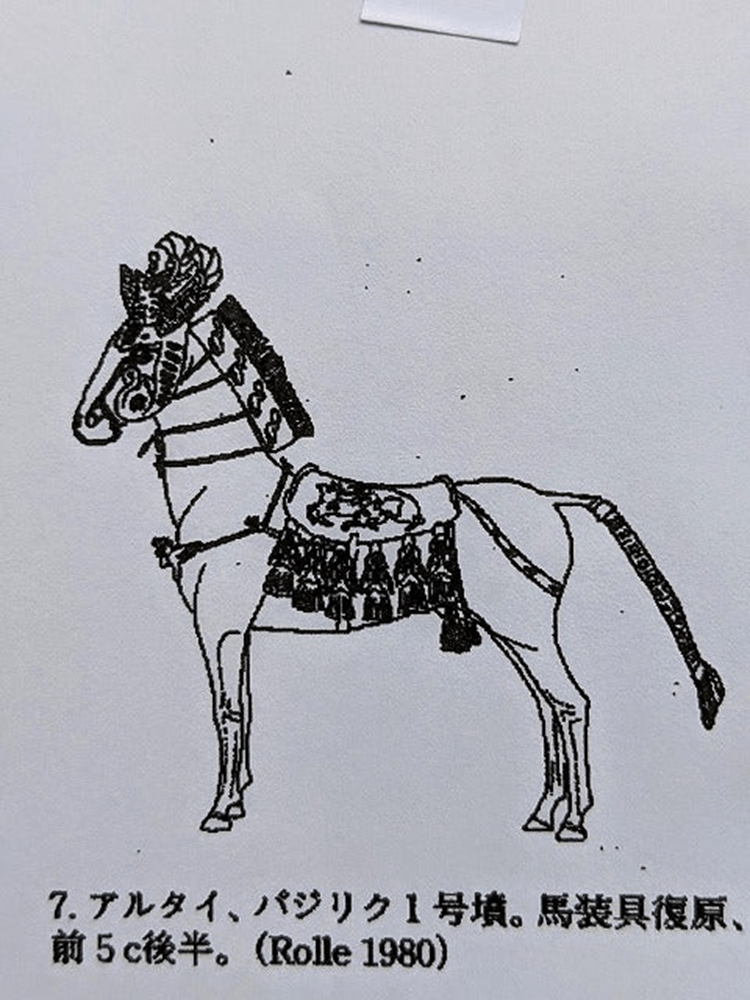

Confirmation of a soft saddle

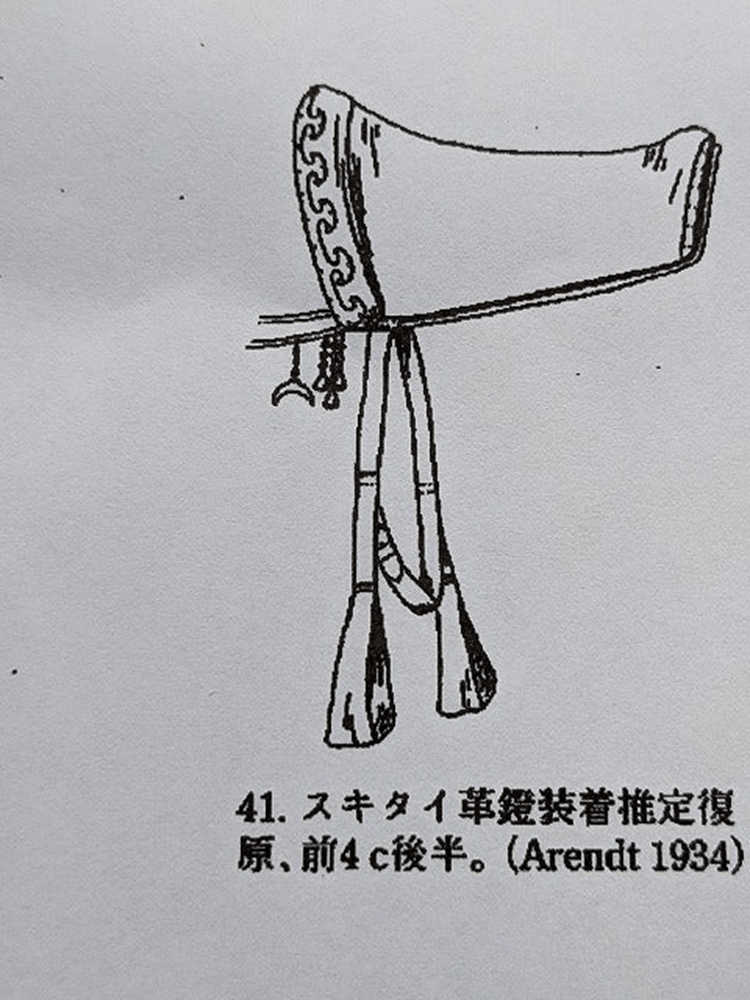

The introduction of the soft saddle likely coincided with King Wuling of Zhao in the fourth century BCE, when he adopted Hu clothing and mounted archery—short tunic-style garments, trousers, and boots suitable for riding, worn by nomadic peoples who shot arrows on horseback. The Chinese character for saddle (an) uses the leather radical, indicating that when saddles were introduced to China, they were made of leather rather than wood.

Rather than a simple pad, the saddle featured slightly raised front and rear ends (though not as pronounced as later rigid saddles) and was secured with a girth and breast strap. Two large pieces of leather were sewn together and stuffed with deer hair (occasionally sedge grass). To prevent shifting, vertical quilting with twisted hair, hemp, or hair cords, or leather thongs, was applied using three rows of stitching.

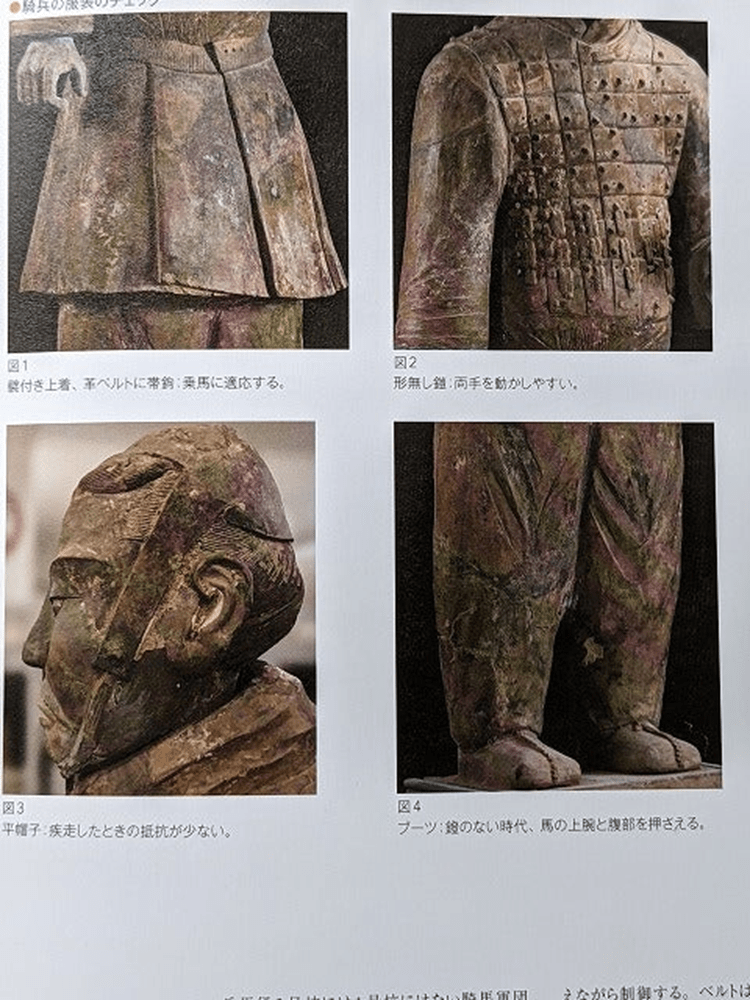

Armored Cavalry Figurine

The cavalry unit holds long-shafted weapons upright in the left hand while controlling the reins with the right. It is said that stirrups did not exist during the Qin–Han period (though reconstructed Scythian leather stirrups suggest that organic materials may have decayed underground). Control was maintained by pressing the instep against the horse’s belly. The lower half of the garments featured front pleats to facilitate riding. Armor lacked shoulder protection to allow free arm movement, sleeves were short and tubular for easier rein handling, and thick trousers extended to cover the feet.

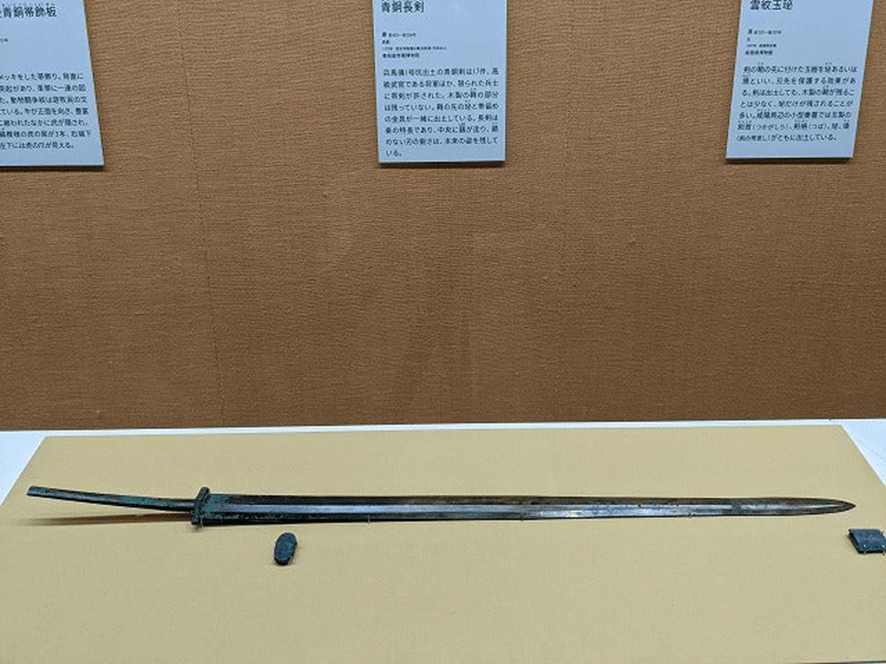

Bronze Long Saber: Total length 90.3 cm; blade length 71.9 cm.

Only generals and select soldiers were permitted to carry swords. Such long-bladed swords are characteristic of Qin craftsmanship. The central ridge and sharp, rust-free edge show no signs of use, preserving the weapon in near-original condition.

B. Former Han Dynasty: Terracotta Figures (Reduced Scale)

Mounted warrior figurine

In 201 BCE, Liu Bang personally led Han forces against Modu Chanyu of the Xiongnu, who commanded some 400,000 cavalry. The Han army was decisively defeated and besieged at Mount Baideng near Pingcheng for seven days. The Han army numbered 320,000, and its defeat was attributed to an overreliance on infantry. Xiongnu horses were said to include white horses in the west, blue-gray in the east, black in the north, and red in the south.

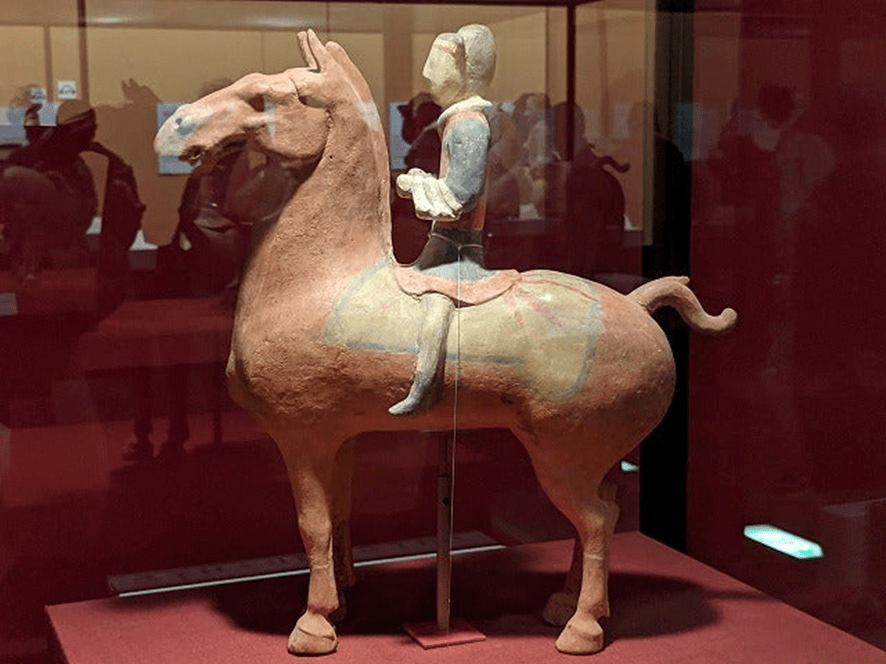

Painted mounted figurine

Height 33.2 cm; length 34.6 cm; width 11 cm

This figure is exactly half the size of the mounted figurines from the Yangjiacun burial pit and firmly grips the reins with both hands.

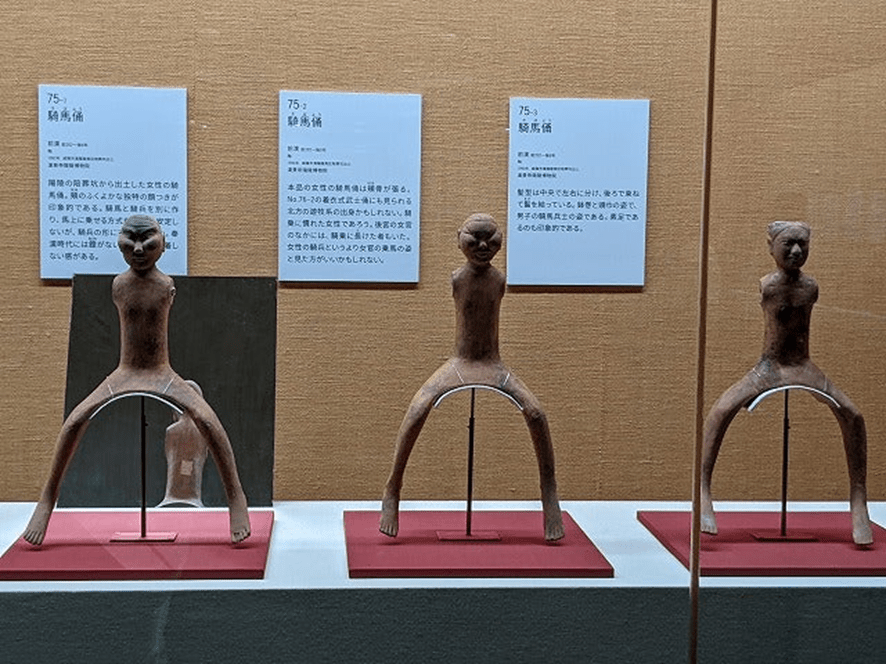

Female mounted figurine

Height 52.5 cm

Her full cheeks and distinctive facial features are striking. The mounted figurines from Yangjiacun press their feet against the horse’s belly.

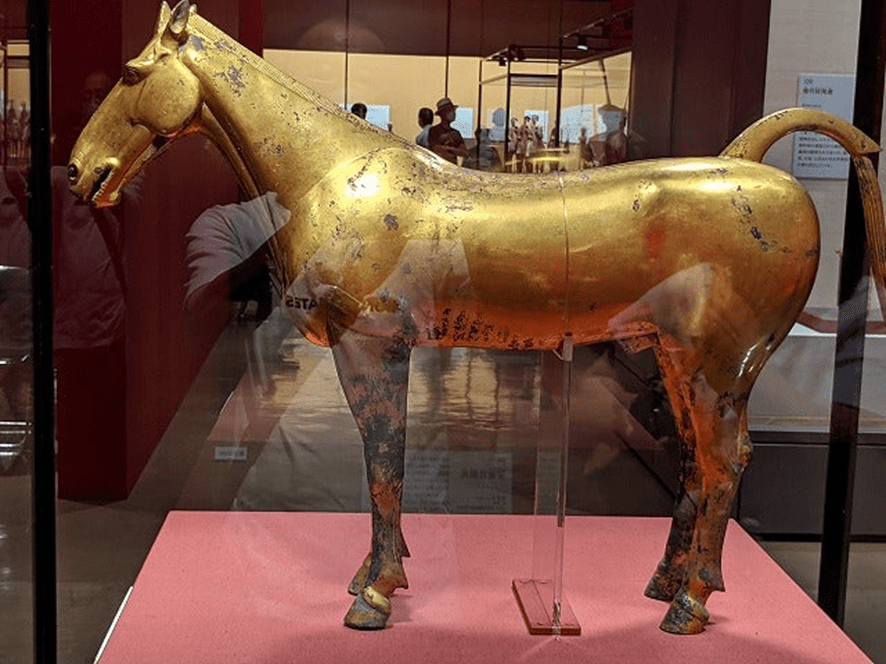

Gilded bronze horse

Height 62 cm; length 76 cm

This horse belonged to Emperor Wu’s sister. It is clearly a Western Regions “sweating blood horse.” Emperor Wu dispatched General Li Guangli to Dayuan to obtain such horses after Princess Yangxin’s death in 101 BCE. The gilded bronze horse is hollow, weighs 25.5 kg, and can be carried in both arms. Its well-developed hindquarters suggest great leg strength.

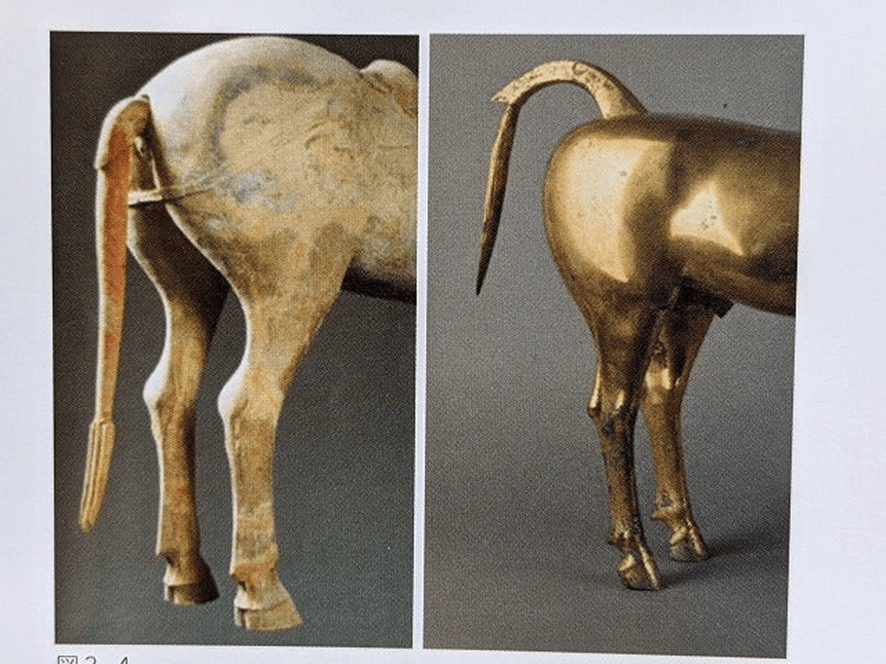

Left: Tail position of the First Emperor’s mounted figurine

The tail contains caudal vertebrae continuous with the thoracic, lumbar, and sacral vertebrae, making this position anatomically correct. The tail position of the gilded bronze horse is unnatural. The base of the tail is bound with a tail bag and braided into three strands, possibly to control an uncastrated male horse. Similar tail treatment appears on the gilded bronze horse.

Note 1: Dayuan is not a direct transcription of a proper noun but likely means “great oasis.” The character 宛 is probably erroneous and homophonous with 苑 or 園. The location is difficult to specify, but it was likely a Central Asian oasis city renowned for horses and grapes.

The region sought by Emperor Wu was an exceptional horse-producing area requiring south-facing mountain slopes for wintering, highlands for summer grazing, and abundant oases. Located southwest of the Xiongnu and directly west from the Han perspective, it was a settled agricultural society with fortified cities, over seventy in number, and a population of several hundred thousand. Armed with bows and spears, it practiced mounted archery and fielded an army of 80,000 to 90,000 troops.

Although the existence of saddles has been confirmed, the presence of bits is equally essential to understanding cavalry tactics, prompting further investigation.

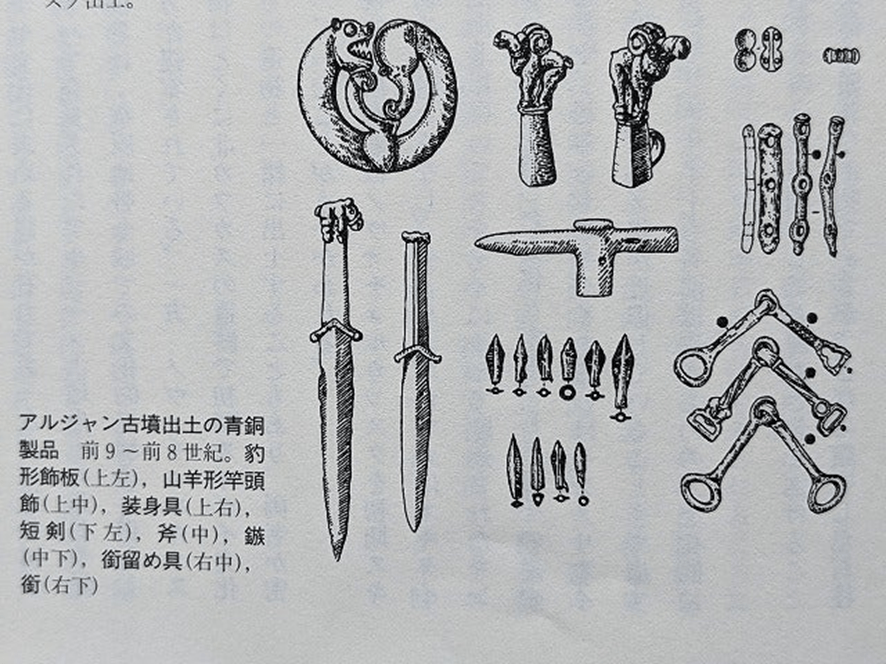

A bit excavated from the Arzhan burial mound

The presence of bit fittings dating from the ninth to the eighth centuries BCE suggests that such equipment was transmitted to the Qin and Han periods.

References:

The Terracotta Army and Ancient China: The Legacy of Qin–Han Civilization

Central Asia: The Crossroads of Civilization, by Shinobu Iwamura

Central Eurasia, by Hisao Komatsu

Saddles and Stirrups, by Toshio Hayashi

The Genetic Background of Native Horses, by Akira Tosaki

Interviews: Nagoya City Museum

September 18, 2022

Sumio Suzuki

コメントを残す